Superheroes. Fantasy. Science Fiction.

Books

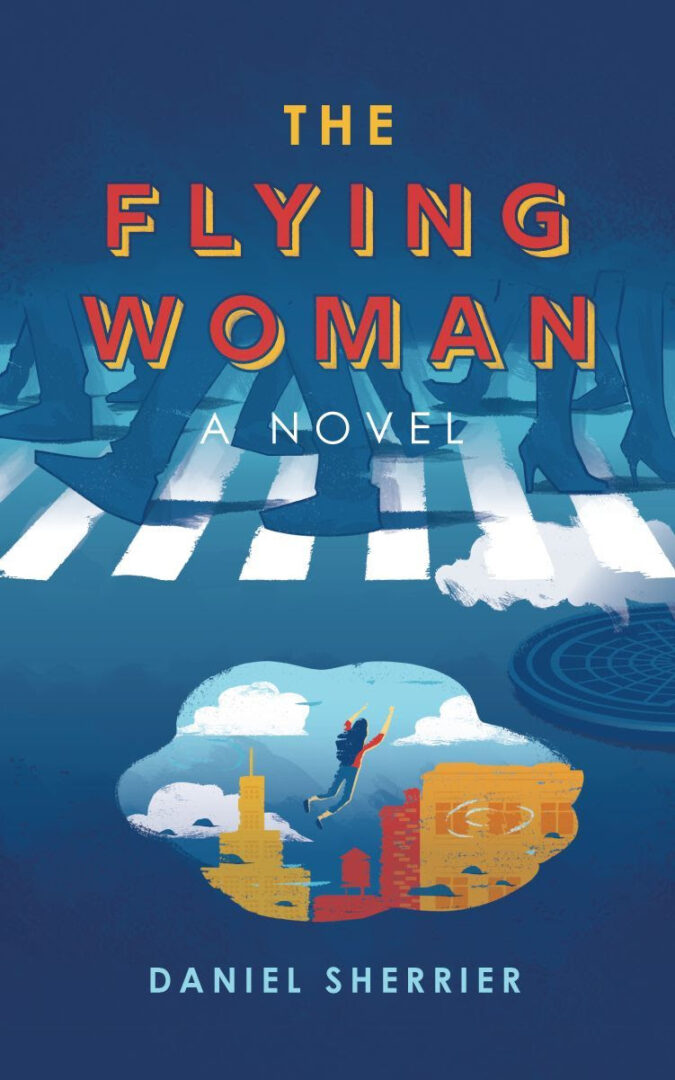

The Flying Woman

The impossible has become a reality! A masked man possesses extraordinary powers, using those fantastic abilities to fight crime and pursue justice. Meanwhile, Miranda Thomas expects to fail at the only thing she ever wanted to do: become a famous star of the stage and screen.

One night, Miranda encounters a woman who’s more than human. But this powerful woman is dying, fatally wounded by an unknown assailant. Miranda’s next decision propels her life in a new direction—and nothing can prepare her for how she, and the world, will change.

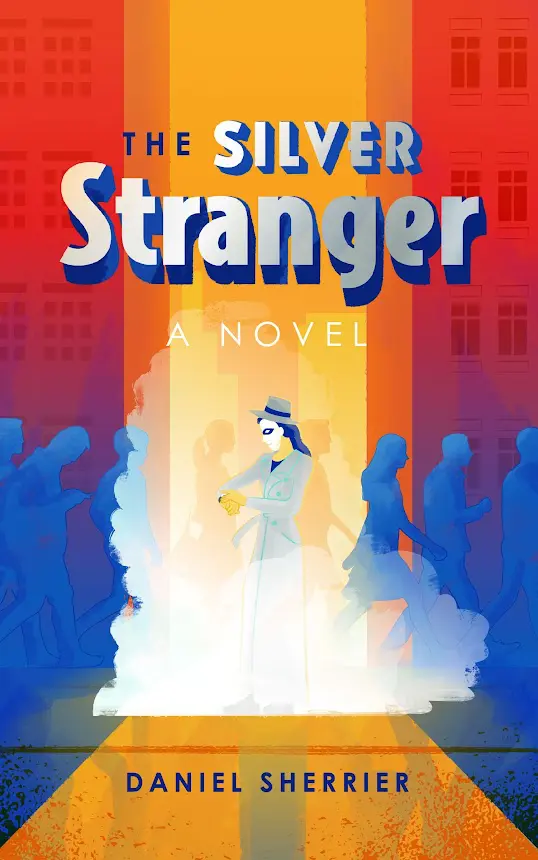

The Silver Stranger

Alyssa Henson hates that superpowers have become real.

She had once dreamed of exploring outer space but kept her feet on the ground and settled for a more conventional life. And now, people are soaring overhead, outracing sound, transforming into photons, and so much more.

It’s unnatural. It’s weird. It’s dangerous. And it needs to stop.

The villainous Doctor Hades agrees. When Alyssa acquires power of her own, she joins forces with the Terrific Trio’s archenemy to erase all superhuman abilities—even those of her heroic best friend—in order to save the world.

In this exciting sequel to The Flying Woman, a new vigilante emerges as The Silver Stranger, a mysterious mind-reader who would rather spy on the thoughts of others than examine her own.

About the Author

Daniel Sherrier writes superhero, fantasy, and science fiction novels. He’s a William & Mary graduate, a former community newspaper writer and editor, and a black belt in Thai kickboxing. And there was that one time he jumped out of an airplane, which was memorable.